About

If you are reading this, you are probably in front of a screen. This text, a tiny spiral of positives and negatives laying dormant on the spinning platters of a hard disk somewhere west of Weehawken, was translated into a signal stream upon your last click of the mouse and sped rapidly over (perhaps) thousands of miles through an intricate routing system to a cable at your address – or to a radio transmitter nearby. Your machine interpreted the incoming signal in microseconds and, as a result, thoughts once in my head are now, almost immediately upon demand, in front of you.

If you are in the internetting majority, my text is likely in a virtual window, or ‘tab’, alongside many others. Each of them virtually connects you to persons, businesses, friends, photo albums, social networks, news, encyclopedias, music players, and almost anything else imaginable, twenty-four hours a day. You and I have a kind of access to persons and information that was not even dreamed of only a couple of centuries ago.

If you don’t like what you are reading or watching, or you lose interest in my thoughts or anyone else’s, you can stop – whether you close the tab, close the program, or just get up and walk away – any time. And as you read, watch, listen, and generally ‘surf’, as we call it (and what an interesting metaphor), advertisers and businesses other than the one you are ‘connected’ to are vying for your attention – eager and hoping for just one glance, one image retained, maybe even one click.

This kind of constant ‘connection’ is at once very flattering and incredibly powerful, and perhaps you feel a sense of this power when you are locating a restaurant in a place you’ve never been – and reading menus – and checking reviews – all from your phone, in between status updates and another round of Angry Birds, while all the calls (inconvenient interruptions which phones were initially designed for) are thrust over to voicemail. Maybe you revel in the freedom, the [seeming] independence, the attention, the control.

But you and I have traded something in exchange for this power.

Because the trade is rarely obvious, and because most of us now view technological ‘progress’ as an end in itself, we tend to accept and implement whatever new device is on offer as an unqualified good – as a benevolent gift.

The makers and sellers of each new technology, platform, or device promise to lessen our workload, improve our communication, increase our knowledge, save us time, make us more attractive, more productive, more up-to-date, and generally more ‘in-touch’. And while we often feel like some of these changes (and many others) are, in fact, taking place when we have purchased or otherwise engaged with these technologies, after a while we begin to notice that our lives have somehow become more complicated, our time more filled, our work harder (or at least more multi-directional), and our relationships more superficial and more strained than they were before.

What happened? What are you and I trading away in exchange for extraordinary power? Why is it so hard to put a finger on exactly what we’re talking about here?

That trade is the substance of my writing, and I would like to talk about it from a number of different angles. I think the trade is one of the most significant dynamics presently operating in our culture – in other words, it’s changing all of us. It’s changing you, right now. And I’d like to help you to recognize the changes and begin to reverse some of them, for your benefit and ours (I am speaking, of course, for all your friends and relations).

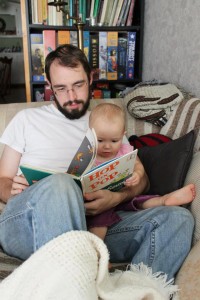

Who am I? My name is Michael, and I’m a professional musician, system administrator, web developer, teacher, church elder, gardener, and (in the words of Ken Myers) a recovering technophiliac. I’m a husband and a father of three. I like parenthetical insertions too much (like this). I’m a bit long-winded, and not less in person than in writing, but lots of my friends seem to appreciate that. Or at least tolerate it.

Who am I? My name is Michael, and I’m a professional musician, system administrator, web developer, teacher, church elder, gardener, and (in the words of Ken Myers) a recovering technophiliac. I’m a husband and a father of three. I like parenthetical insertions too much (like this). I’m a bit long-winded, and not less in person than in writing, but lots of my friends seem to appreciate that. Or at least tolerate it.

I was homeschooled for many years.

I am passionate about helping people become more culturally aware and take their lives back from the machines that have occupied them.

I am very concerned about our food, about the state, about the banking system, and about how much most of us don’t know about all those.

I hope that what I write can help you – help us together – to recover what is essential, in the givenness of the natural order, to being human.

3 thoughts on “About”